My friend, writer Mandy Haggith, has recently published a very interesting book about elm trees.

My friend, writer Mandy Haggith, has recently published a very interesting book about elm trees.

Like me, Mandy lives in Assynt, and while researching the role of elms in Asia, had discovered that taiko are traditionally made of Japanese elm. I told her what little I knew about taiko making and gave her a wee taiko demo, which she has written about beautifully.

She later told me that discovering there was a taiko ‘root’ here in Assynt helped her write her chapter on ‘Elms Around the World’. For me, it was inspiring too. I hadn’t been playing taiko much, due to a slow recovery from an injury. When she sent me a draft of the passage she’d written, I was moved to discover she’d captured all the elements of taiko which drew me to it in the first place—the simplicity, the power, the balletic grace—and this inspired me to resume playing again more regularly. A fortuitous connection for us both.

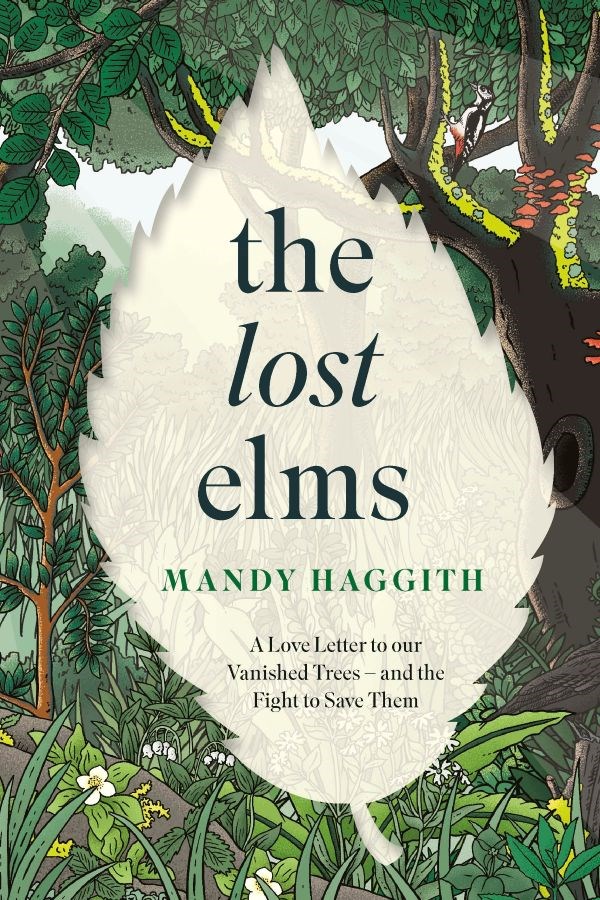

As for the book, it’s wide-ranging. As well as detailing the immense losses of elms to Dutch Elm Disease, she chronicles their role in geography, culture and history around the world, along with attempts to re-establish viable populations of elms. It’s an intriguing and uplifting book and is well worth a read, and not just for the taiko connection.

As we saw in chapter 2, the elm family includes a group of trees called zelkovas. One of these (Zelkova serrata) grows in Japan and is known as keyaki in Japanese. It is used to make a big drum, called the nagado daiko, one of the special instruments for the traditional art of taiko, a musical performance that involves a group of players making a lot of noise with hollowed-out tree trunks, animal hide and big sticks. My friend Alison Roe performs and teaches taiko drumming, and she gave me a brief demonstration on her own nagado drum. Nagado means ‘long body’ and the drum is almost a metre tall, and fat as a Buddha, a big presence in the room. Alison is lithe and petite – she looks as if she would play a delicate little instrument, a flute perhaps. She approached the drum in a nonchalant manner, then broke into a dance. Her sticks flew and pounced and spun as she performed a kind of ballet, her entire body flowing with a complexity of movement at once effortless and profoundly formal, and out of this fluid motion came an extraordinary range of sound: a voice murmuring and tapping, clicking and hammering, booming and roaring. Her ceremonial dance was transformed by this big, shining, beautiful round instrument into song. It was a brief but mesmerising display. I remember once seeing a taiko group at a festival and being blown away by the athleticism of the drummers, the complexity of their rhythms, the sheer noise of the massed drums and the ancient power of this ritual performance.

Alison said, ‘Since, in Shinto, every natural object has a kami (spirit), a taiko therefore has a spirit, composed of the spirit of the tree its body came from and the spirit of the cow its skin came from, so when you play a taiko, you’re playing with its spirit’. The making of taiko is an art form in its own right, and it can take four years from the felling of a zelkova tree to season the wood, hollow it out, shape and decorate it, carving the inside of the drum to give it its perfect sonic signature and then skinning it with leather.

NOTE: My own taiko is not made of Japanese elm (Zelkova serrata) but is a Californian wine barrel, expertly made into a lovely nagado by Kato Taiko in the US. I do aspire to have an elm taiko, however. When I visited my taiko teacher, Kurumaya-sensei, in Japan in 2014, he took us to the Asano Taiko factory, makers of the best taiko. One day…